Today I had the honour of giving a talk to the illustration students at the University of Gloucestershire! I did the first in a series of Visiting Artist Talks in the massive lecture hall at Francis Close Hall. Huge thanks to Tom and Kim for inviting me and facilitating the event, and thanks to the illustrators for coming to watch and listen (and especially to those who played bingo and/ or gave me your feedback!)

The itinerary!

I started my BA in Illustration at the University of Gloucestershire in 2012. In my final year, our then head of department KP wondered about setting up the MA, for which I was well game - I wanted to see where I could take my illustration practice next, how I could push it in new directions, how I could use it for research. Then, towards the end of the MA, we started wondering about how the Illustration department could do a PhD - then there was a year of trying to get it off the ground - and then eventually, in the autumn of 2018, I started it!

This is the bit where I ask everyone if they've heard of Charles Dickens. Then I ask if they've heard of/ read/ seen an adaptation of/ etc Nicholas Nickleby. That's most people's gateway into the Yorkshire schools.

Here's where I give a brief overview of the Yorkshire boarding schools - popular from c.1750 to c.1850 - usually aimed their adverts at middle-class parents in cities (often London) - reasonably priced (compared to some schools like Eton and Harrow and that) - also the curriculum is broader (and more useful) than those expensive schools, covering stuff that you'd need if you're going into a mercantile profession or whatever.During the last year of my BA (2014-15), for my final major project, I researched, wrote, and drew a nearly-finished graphic novel about the terrible misadventures of a fictional boy at Bowes Academy. I went to archives, did site visits, generally had a great time... Unfortunately I was still heavily influenced by Dickens's Dotheboys Hall, and I had no idea how historians do what we do (I thought it was all about Finding The Facts haha wtf) and the result, Bad Form, contained interpretations that I no longer support. (I'm glad I never finished it and it never saw the light of day.)

One of my reasons for doing my PhD about this case study was to see how my interpretations had changed. This slide shows how my depictions of Bridget and William changed (and my drawing style too). At the top of the slide is a panel from Bad Form (2014-15), and then in front we've got Bridget and William from about 2019.

This was great - I asked the illustrators to shout their ideas at me, and fortunately they all said very sensible things about creating interpretations, going on site visits, viewing things in museums, and interviewing people who were involved or whose relatives were involved. I am relieved and delighted to say that nobody came out with any nonsense about 'finding the facts to tell the true story about what really happened in the past'!

We make evidence-based interpretations of traces of the past, using a load of other considerations! Unfortunately not everybody likes to acknowledge these. It's usually your more traditional historians who tend to forget themselves and their subjectivity and creativity and imagination and such in creating their interpretations.

The past is gone and we can't get it back (which is not a bad thing when we think about various embarrassing situations). History is what historians make: it's how we communicate our ideas about the past.

Single statements and broader interpretations! A single statement is more usually known as a 'fact'. This is a small thing. A work of history (usually containing a number of these) is a broader interpretation. For instance, this could be when your historian has put a bunch of single statements together and needs to join them up somehow, or when they've decided that this specific statement definitely means this, or when they build a narrative out of things - anything like that.

We don't know what kind of teacher Mackay was! That's the broader interpretation. I can suggest different ideas about him using drawing, but these are interpretations, not facts. (I like to interpret him as being very enthusiastic but I genuinely have no idea.)

Neither of these things are William Shaw. One is a couple of words. The other is a drawing of a character that I created to represent my interpretations of what he might've been like at a certain point in his life. Neither of these are the man himself.

Every event will have multiple perspectives: everyone involved (or who witnesses it or hears about it later) will have different experiences and interpretations and such. Then we can have fun with memory, and with how they relate their tale/s to others, how they make sense of it themself, whether they can commit it to the historical record, whether it survives, who has power over which stories are preserved and which stories are told...

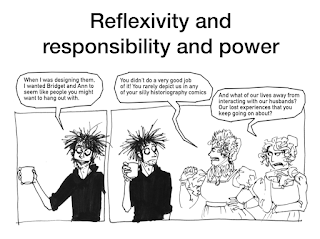

Which leads onto one of the uses of being reflexive about your practice, and thinking about what you do and how you do it: you become aware of your own responsibility and power in how you depict (your interpretations of) the people and events in your case study!

Making your characters self-aware (aware that they are invented characters) is a useful strategy - it points out that, unlike what some more traditional (and anti-theory) historians might say, the history is not speaking for itself. These people are characters who I've made, and they know it. (Well, they themselves don't really, because they're made of ink, but anyway.)

Here's a thing that more conventional historians might find a bit trickier if they prefer to do things in writing - using yourself as drawing reference! I have limbs, I have a camera, I make my own pose reference.

By this point, I've been working with some of these characters for so long and at such intensity that it feels like they're just out of reach - they're part of my imagination, they contain parts of me, some of them are now part of me - but their originals are in the past and I can't access them because they're dead.

Blog post about the historical sublime here!

An example from my work - in the early 1830s, Charles Mackay stopped working for William Shaw. I have no idea what happened. This is another gap for imaginative exploration. (I don't know whether they had a row or what, I just like drawing angry people and teeth)

- Rethinking History journal - available via the university's library page, or via Taylor & Francis (login via institution, search for Rethinking History, job's a good'un) - this was set up by Alun Munslow and friends, and has loads of really good articles about historical theory and loads of fantastic experimental history too - for instance, this issue is about graphic novels as history (and was edited by one of my examiners!), and this experimental article is a comic exploring exciting things including metaphor, multiplicity, self-awareness, and the fun you can have with images (and was illustrated by my other examiner!)

- Library shelfmarks 901 (philosophy and theory of history) and 907 (historical research) - more fun things about how historians do what we do.

- Work by people such as Alun Munslow (Deconstructing History and Narrative and History are good places to start), Keith Jenkins (Re-thinking History is an excellent primer), Robert A. Rosenstone (does a lot of stuff about film and history, might be useful for different approaches to visual storytelling), and Ludmilla Jordanova (does a lot of very splendid work on using visual and material culture in creating historical interpretations).

No comments:

Post a Comment