Remains to be seen whether this will end up as a series or not. Anyway!

The Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c. 1500 - c. 1800

Nigel Llewellyn

Reaktion Books in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1991

Copiously illustrated with all manner of splendid deathly items from visual and material culture: coffin plates, engravings, commemorative portraiture, effigies, monuments, mourning rings, sketches, and loads more. There’s also a few references to things not shown in the book that can be tracked down later.

The text itself has some concepts that can help contextualise death and the mentalities and practices surrounding it. I’m particularly interested in the two bodies - the social body, which is the form of the deceased as remembered by everybody else (such as in commemorative portrayals, epitaphs, and stuff designed for future viewers), and the natural body, which is the bit that rots and has the potential to cause alarm with its decay. The social body, as presented in monuments and what-have-you, could sometimes be used to communicate a revised version of the depicted individual’s life and exploits. Weirdly, history might count as presentation and re-presentation of the social bodies of people in the past, according to historians’ interpretations and their own cultural contexts and all that.

|

The concept of the two bodies concerns image control, reputation, what people in the past wanted their contemporaries and people in the future to remember (or to believe) - that sort of thing.

Yeah, the title says the period the book covers finishes circa 1800, which you’d think would put it a bit too early for my case study, but there’s a fair amount of stuff I’d find useful anyway. There’s a few post-1800 things, and plenty of stuff that I can pull into my work that people of the time would have understood. I came away with loads of ideas, particularly with regard to William and his potentially forthcoming death in Despaired Of - my weird experimental comic in which one small aspect of an incident at Bowes Academy is explored using five different visual languages - basically, William’s life was “despaired of” at one point, and they thought he was going to die, so this book is setting my brain on fire (in the best possible way) with all sorts of wild stuff.

|

| Bridget in a state of neoclassical despondency. |

Pagan Britain

Ronald Hutton

Yale, 2013

Not gonna lie, I’m a fan of Ronald Hutton. I’ve attended a couple of his talks, and I read The Triumph of the Moon in the summer, and, as far as I’m concerned, he says a lot of very sensible things.

Pagan Britain is a good solid overview of belief and its material traces from prehistoric times, through to the Middle Ages, and with a few hints of seemingly pagan practices in later years.

(“What are you reading this for, Ed? This is all well before your case study!” exclaims the reader, much surprised.)

I’m in strong agreement with Hutton’s historiographical angle. He declares his standpoint, respectfully, at numerous points in the book. He acknowledges that there’s multiple interpretations of the traces that are left, and how those interpretations have changed (and will change) over time, and that we’re not going to get the final story of any of it. He presents various interpretations, archaeologists’ arguments, and so on, displaying the pros and cons of them and giving them a fair hearing, and he also shows us his own thoughts on various matters - sometimes he explains which interpretation he prefers, or he reacts with quiet emotion to one of the possible stories of what might’ve happened, rather than hiding and feigning objectivity. Basically, he says a lot of things I agree with! Especially in his conclusion - flippin’ ‘eck, it’s a glorious few pages, brilliant and concise, and can be applied to history in general rather than being limited to the scope of the book.

|

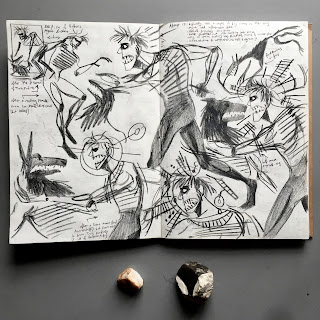

The illustrations in this book are fantastic, and have given me all sorts of ideas for Charley's visual language in Despaired Of.

There’s also the visual side of it. There’s plenty of illustrations, including a lot of prehistoric rock carvings, abstract motifs, and representational art. There’s drawings or photographs of amazing things regularly throughout the book. Interestingly, the figures aren’t always directly referred to in the text - I didn’t notice any “see fig. 24” or anything - so the images run alongside the text, and could be viewed almost as a separate essay in their own right. This book has been vital for some of the sections of Despaired Of - one of the characters has an almost prehistoric visual language, in a recontextualisation away from the early 19th century setting.

|

| Charley confronts a metaphorical wolf that's been saying nasty things to him. Told you Despaired Of is weird. |

Witches & Wicked Bodies

Deanna Petherbridge

National Galleries of Scotland in association with the British Museum, 2013

This is a catalogue to accompany an exhibition (that, of course, I missed) and it’s full of depictions of witches, from the Renaissance to the early 21st century.

The images provide a fascinating exploration of how witches were usually depicted by artists in order to convince their audience that they were definitely evil, although these works probably acted as further evidence confirming some of that audience’s pre-existing suspicions. They might’ve said things like ‘Those witches are definitely up to no good - I saw a picture of it!’

And what type of people are the witches in the illustrations? Almost always female, typically either quite elderly and rather unprepossessing, or youthful and somewhat provocative. Both of these depictions are intended to communicate the evils of witches: the ugliness of the more venerable ones is equated with their wickedness, while the young witches are intent on ensnaring blokes with magic spells and sexiness. (It seems that people in the past were a bit scared of women having any sort of power. I hope we’ve moved on from that way of thinking.)

|

This is my favourite image in this book - The Weird Wife o’ Lang Stane Lea (1830) by James Giles (1801 - 1870). I love this because there’s a witch (of course!), there’s a megalithic monument, there’s the moon and (presumably) Venus in a wonderful sky, there’s dramatic light and shade - there’s all sorts of narrative potential in this painting, things to wonder about, especially with regard to what secret things the witch might’ve just done - and it was painted during the early 19th century. Wins big points from me.

What if you’re not into witchery? This book will show you a curated group of images that document (often negative) views of women’s bodies over a set period of time. Or you could read it with the illustrator’s eye, and look for things that you can borrow or subvert in your own drawings, as a reaction to the images you’ve just seen. Or you could see how methods of image-making change over time, and what media gives the most striking results for the creator’s intent for the image. Or you could have a close look at the images in terms of their material culture, and see what sort of things people wore (or didn’t, there’s a lot of nudity, but we can all handle it like grown-ups) or associated with occult practices.

No comments:

Post a Comment