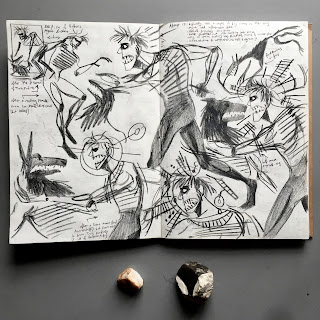

Using Phiz's illustrations. I think VIBE CHECK is my favourite.

Thursday, December 31, 2020

Wednesday, December 23, 2020

The Society for Theatre Research did a Zoom production of Nicholas Nickleby and it was Good

Earlier this month, I went to the theatre - without leaving the house! The Society for Theatre Research held an online performance of Edward Stirling’s 1838 adaptation of Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby, with a versatile and enthusiastic cast. There was a brief contextualising explanation at the start, and then the performance kicked off - and what a performance it was - and you can watch it here!

The company all had great fun performing, and all communicated their characters very effectively over Zoom, with appropriate subtleties and exuberances as required. They were very properly attired, with a splendid profusion of hats and other accoutrements, and a fine range of suitable props - sometimes it looked like a big Victorian video-chat party, which I suppose it was - and it was all excellent!

The script was that of the first ever adaption of Nickleby, and was first performed well before Dickens had even finished the novel. (The whole text of the play is available to read here!) Every month from March 1838 to September 1839, a new instalment of Nickleby would come out, containing a few chapters, two illustrations by Dickens’ mate Phiz, and a bunch of adverts and extra bits, and each instalment would cost one shilling (except the last, which was a double number and cost two). In November 1838, Stirling’s adaptation premiered at the Adelphi Theatre, on the Strand, in London.

Given my research interests, this post is mainly going to be about contextualising the first stage depiction of Wackford Squeers, comparing this with Nickleby and with some fragments of information about Yorkshire schools, and some ideas I had after watching the STR's performance.

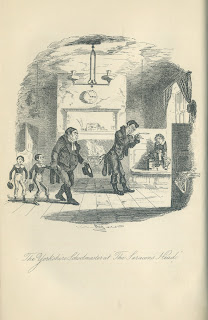

The play opens in the Saracen’s Head, Snow Hill - a coaching inn - and we’re immediately introduced to Mr. Squeers (played by Mark Fox in the STR's version), a Yorkshire schoolmaster who quickly establishes himself as a villain, generally being disagreeable (with a façade of benevolence) in ways that Nickleby readers will recognise from his first appearance in the novel in Chapter 4.

Upon the arrival of Ralph Nickleby (played by Steve Fitzpatrick) and his nephew Nicholas (Hugh-Guy Lorriman), Squeers begins to reel off his advert, as he does in the book, and which the 1838 audience would have recognised from schoolmasters' adverts they'd have seen in the newspapers.

The schoolmaster also explicitly mentions two towels in the first scene, while in Act 1 Scene 3, he says that the inhabitants of Dotheboys Hall get up at seven in the morning during winter, and six in the summer. However, comparing this with Nickleby, in Chapter 7, he only mentions getting up at seven - nothing about six - and isn't specific about the number of towels. Now, anybody familiar with the finer points of the 1823 ophthalmia trials (in which William Shaw was taken to court by two families for allowing their sons' sight to be damaged) will recognise the two towels - Shaw only provided two for his entire school of nearly 300 boys. We don't have the precise getting-up times at Shaw's place, but we have these times from other schoolmasters; for example, Mr. Simpson of Woden Croft, just up the road from Shaw's, specified that his scholars should get up at 5:30 in the summer and 6:30 in the winter. I reckon Stirling Knew Things.

Squeers also recites a list of items that the boys need to bring to his establishment, as he does in his initial appearance in the novel, and which echoes a list on a card of terms from William Shaw's Academy that turned up in an issue of the Dickensian. (And I am much vexed as I don't know which issue it's in and I can't cite it properly - I have lost the original PDF - iCloud has taken to betraying me of late - but I will get hold of it again.)

I’m not sure whether Yorkshire schoolmasters had appeared on the stage before Stirling's adaptation, but, if not, this is likely to have been the first time a lot of the audience had encountered a depiction of them outside their newspaper adverts, word-of-mouth tales, and Phiz's Squeers in print-shop windows.

This page from the Adelphi Theatre Calendar says that a ticket for a seat in the upper gallery cost one shilling, two for a seat in the pit, and four for a seat in a box. If you spend one shilling on an instalment of Nickleby, you get a few chapters, a couple of illustrations, etc., whereas if you spend it on a theatre ticket, you get a few hours of a variety of different entertainments, and you don't have to fork out for all the other instalments of the novel to find out what happens next in the story. There might've been people in the audience who were reading the novel and wanted to see it acted out before their very eyes, and there might've been people who went for a night out or to see some other anticipated performance and went home with a head full of Dickens, and there might've been people who were like "I've not read it, but I'll watch the adaptation".

I reckon that this play could’ve potentially contributed to public perceptions and opinions of Yorkshire schoolmasters and their establishments. There’s a few scenes at Dotheboys Hall - which would’ve been depicted wonderfully grim on stage, as the early 19th century theatre delighted in impressive sets -complete with the forbidding Mrs. Squeers (in the STR's 2020 version, played with vigour by Sunita Dugal) and a cortège of miserable boys (mainly voiced by the STR's Eileen Cottis) - which would have communicated a version of Dickens and Phiz’s interpretation of the Yorkshire schools to a broader audience.

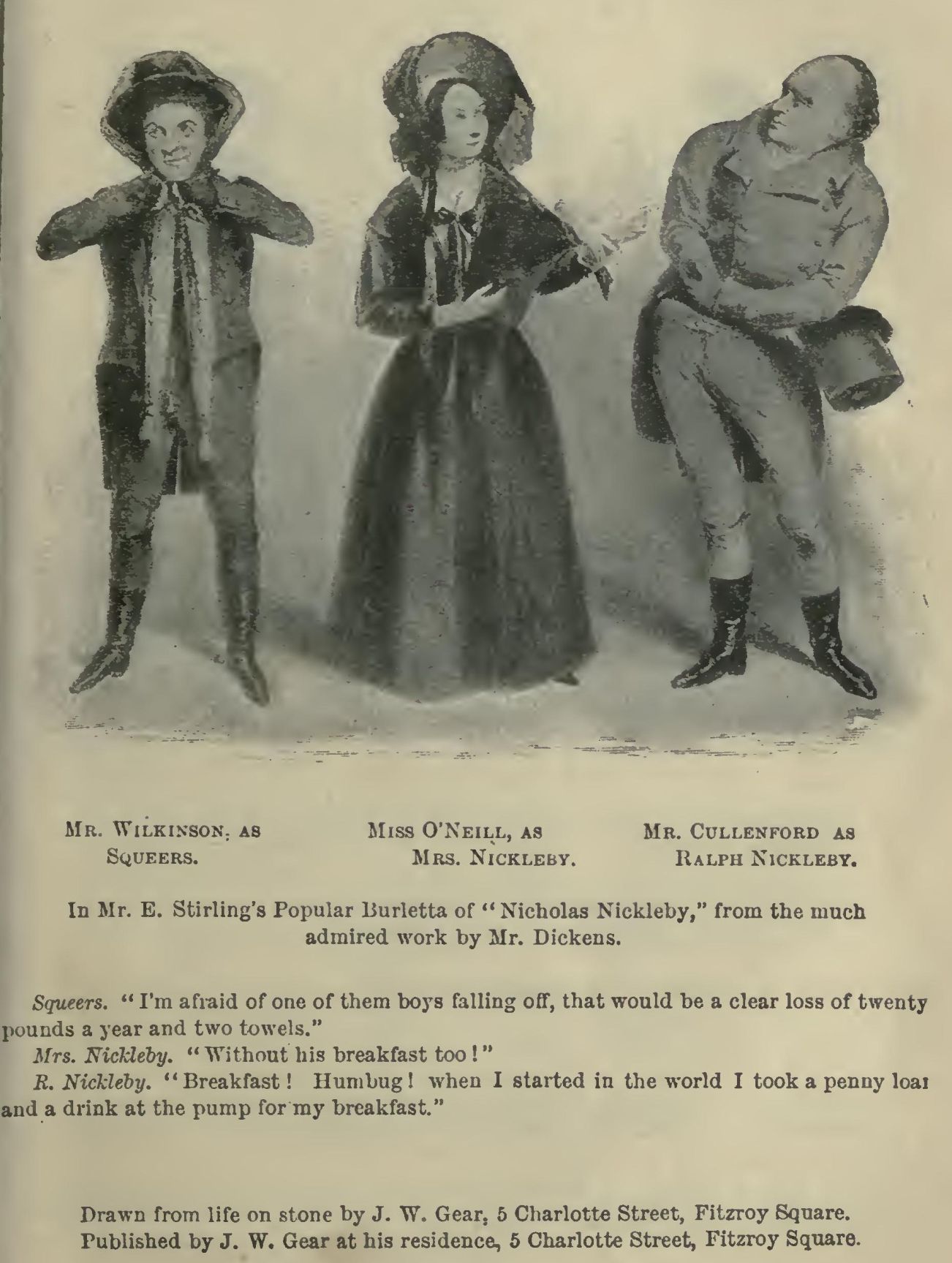

The original 1838 Squeers was played by James P. Wilkinson, who joined the Adelphi’s company in 1819, and whose last performance was in 1845. Having quickly eyed his entry on this page, he seems to have done a lot of burlettas, comedies, and similarly amusing productions, but he wasn’t unfamiliar with more serious dramas and melodramas.

|

| Here's a page from Project Gutenberg's edition of Nickleby - Gear's illustrations are in the front, accompanied by quotes from the play rather than from the book. |

Given the presentation of Squeers at the start of the play, and especially how Stirling’s production’s full title was Nicholas Nickleby - A Farce in Two Acts, the audience might’ve expected the schoolmaster to be more comedic. And yes, the character is funny, in both the original Nickleby and Stirling’s adaptation, but his malevolence soon becomes one of his distinguishing features (after the solitary eye). They certainly expected it of the original Smike, played by Mary Anne Keeley, a popular actress who specialised in comedy; the STR’s introduction explained that, as stated in Keeley’s autobiography, when she first appeared on the stage in the role, the audience expected comedy and roared with laughter - but, after she’d delivered a speech (about being trapped at Dotheboys Hall, with a lot of the “Pain and fear!” bit from Chapter 8) the audience fell dead silent, apart from a single stifled sob…

On Sunday night, the actors explained that the original script contains directions for tableaux vivants - everybody on stage freezes and holds a position, usually in silence - a good modern example is those scenes in A Field In England (directed by Ben Wheatley, 2013, would recommend). In the original performances of Stirling’s adaptation at the Adelphi, the tableaux vivants were arranged to be as close to Phiz’s illustrations as possible. So, thinking about Act 1 Scene 1 (in which we are introduced to Mr. Squeers), that tableau could have represented this scene, but he’d be dealing with breakfast rather than mending a pen:

(As an illustrator, I think this is pretty great. From my perspective, it’s like saying that the illustrator’s work is as vital to understanding the narrative as the author’s. Eh. I’m biased towards my vocation and my fellow practitioners. And I suppose it’s convenient for actors if they’ve got a visual framework ready made for them, and some of the audience will recognise the scenes from their copies of Nickleby, or from the engravings displayed in print-shop windows.)

To my astonishment, the STR actors did a tableau vivant! On Zoom! Everybody in separate locations! In the middle of the scene in which Smike (played by Rebecca Farrell) is captured and Nicholas batters Squeers - that’s not a spoiler, it’s probably the most well-known bit of the story - but the way that they did it was fantastic, quite ingenious and very professional. In the original production, this tableau was based on Phiz’s illustration to Chapter 13.

|

| Imagine this - ON STAGE. |

Alright, yes, this isn’t going to be exactly like what the first audiences would’ve seen back in 1838 - if you want to see exactly what they saw, then you’ll have to invent reliable time travel, but even then you wouldn’t have access to all their cultural references and mentalities and associations and what-have-you, so you won’t get exactly what they’re getting. A step down from time travel, full-scale historical experience replication would take up a lot of resources - rebuilding the Adelphi precisely as it was, finding the scripts for the rest of the evening’s performances, etc. - although it would be fun - anyway! This was a very 2020 version, conducted over Zoom (with one or two technical incidents, but that's all part of the video-chat experience, and the show went on regardless) and it was brilliant.

So, yeah. Not only was it a good night in, but the Society for Theatre Research’s performance might’ve given me a few clues and ideas with regard to public perception of Yorkshire schoolmasters.

Watch the full STR production here!

(Yes, I am including the link twice, because it was that good.)

More information from the STR.

STR's cast list, and list of scenes.

The British Library has a playbill that mentions Stirling's adaptation from February 1839 - the play was still in its first season, and ended up running for nearly a hundred nights.

The British Library also has an original script, with a frontispiece.

Thursday, December 10, 2020

Let's draw William Shaw

Alrighty, so in this post I’ll show you how to draw the ‘protagonist’, I suppose, of my case study. The methods I use here can also be used on other historical people.

Rather than your standard how-to-draw-a-human tutorial (start with a vague skeleton, etc.) I'm going to show you how to get an idea of what somebody might've looked like, drawing from a load of historical sources. I'll include a few sources relating to William, so you can join in, and use him to practice on. How you interpret those sources is likely to be different to how anybody else does, so if you join in, don't worry if your version looks different to mine!

This is William Shaw. He was born around 1782, probably in London (although there’s suspicions that he may have had familial connections with the Teesdale area). He ended up running Bowes Academy from 1814 to 1840. In 1810, he married Bridget Laidman, who came from a local farming family, and they had nine kids together. William and Bridget are buried in the same plot in St. Giles’ churchyard, Bowes, together with their son William. (I tend to refer to the latter as Will to avoid confusion!)

So how do you draw this here schoolmaster?

Luckily for us - not so luckily for him - a couple of chaps called Charles Dickens and Hablot Knight ‘Phiz’ Browne took a bit of an interest in his school.

Dickens had heard horror stories about cheap boarding schools in Yorkshire and wanted to write about them, and expose these horrors to the public, so he and his illustrator friend Phiz went up on a research trip. (Research in the loosest sense of the word.) Anyway, they went under false names, asked questions, heard stuff from people, and one thing led to another, and they got a good look at William Shaw - they went to visit his school, hoping for a look around.

|

| This image is from a presentation I gave to my local history society in March 2020, right before the first UK lockdown. |

However, William had heard there was an undercover journalist from London sniffing around the area and didn’t want anybody sniffing around him (he’d been taken to court in 1823 for neglect, and it’d been widely reported in the newspapers, and he didn’t want all that dragged up again) so when they knocked on his door, he sent them on their way. But they’d seen him - a short, somewhat unorthodox-looking chap, with one functioning eye - and that was enough for them.

William’s appearance turned up in the first instalment of Nicholas Nickleby, turned up to eleven and given the name Wackford Squeers. This was catastrophic for him and Bridget and the Academy - the parents in London recognised that there’s only one one-eyed schoolmaster in Yorkshire, and believed every word of Dickens' tales of woe…

Anyway! We’re here to draw William Shaw, aren’t we? Right! Let’s get cracking!

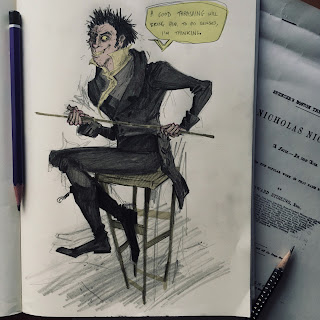

First, we’re going to look at Phiz’s first illustration of Wackford Squeers. Some of his ex-pupils, and even Phiz himself, said that this character strongly visually resembled William, but somewhat exaggerated.

|

| The Yorkshire Schoolmaster at The Saracen's Head which would've been part of the first instalment of Nicholas Nickleby. There's Mr. Squeers, pretending to mend a pen. |

Here’s how I worked out what I think his face looked like: I drew Phiz’s version, then ‘translated’ him into my own visual language (drawing style), and then de-exaggerated him to get the result.

Next, we’re going to look at this quote from actor Horatio Lloyd. He attended Bowes Academy in the early 1820s, and grew up to become an actor. He said William was “a most worthy and kind-hearted, if somewhat peculiar, gentleman” and described the schoolmaster in his memoirs, published in the 1880s:

“A sharp, thin, upright little man, with a slight scale covering the pupil of one of the eyes. Yes. There he stands with his Wellington boots and short black trousers, not originally cut too short, but from a habit he had of sitting with one knee over the other, and the trousers being tight, they would get "ruck'd" half way up the boots. Then the clean white vest, swallow tailed black coat, white neck tie, silver-mounted spectacles, close cut iron-grey hair, high crowned hat worn slightly at the back of his head - and there you have the man.”

(Click here to read Lloyd’s account in full.)

Lloyd has just given us a decent description of William’s clothing, along with one or two hints about his behaviour; he also mentions his dodgy eye, which indicates that Lloyd attended Bowes Academy following the ophthalmia fiasco. However, before we start on William's clothes, we need to think about his body - you need something to put the clothes on!

|

| When I draw people in the wild, I automatically draw them in the costume of whatever time period I'm into - in this case, everybody gets Regencified. |

As an illustrator, it’s a good idea to observe the people around you - under ordinary circumstances, I’d recommend going out onto the street and drawing people in the wild. They just go about their business and you draw them. But - we are not in normal circumstances! I’m writing this in the middle of a pandemic. You might need to get your refs elsewhere. Watch how people move on the telly, or check out Instagram for people doing cool poses and what-have-you.

Now we need to get references for his clothing. Get onto the online databases for museums! Check out re-enactors and historical costumers! Find contemporary images of people wearing similar stuff! Go window-shopping online or in books, whatevs, and try him out in different coats and such.

Here’s three of my favourite museum sites to start you off:

Rijksmuseum (You can make an account on here that’s a bit like Pinterest in that you can make collections and save things that you find, and you know it’s all decent and properly checked because it’s the Rijksmuseum and it hasn’t been saved by randomers from across the internet.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

(Pro tip: when you’re drawing anything from museums, etc., keep note of item numbers, which museum it’s in, date of manufacture, artist’s names, etc. - this will save a few headaches when you want to have another look at a really good coat or something later, and you can’t remember where you found it.)

Alrighty, so you’ve got some more solid stuff: you’ve got an idea of his face, you’ve given him a body, and you’ve put clothes on him. Now what? Make him do things! And the great thing about drawing is that you can make him do anything! You are in control of the pencil, or pen, or whatever. What’s he going to do?

We could ask Lloyd first.

“[William Shaw] would walk around the school room, look over us while writing, and here and there pat a boy on the head, saying "good boy - good boy; you'll be a great man some day, if you pay attention to your lessons." If a lad was ill, he would sit by his bed-side and play the flute - on which he was an adept - for an hour or two together to amuse him.”

Sometimes I think Lloyd’s a bit rose-tinted in his remembering, and I don’t entirely trust him because he’s convinced that none other than Charles Dickens attended the Academy - which is a load of wack. Anyway, let’s have a look at some other stuff.

What if we think about our own experiences at school? How did the teachers move around the room? Did they stride about, or get excited about what’s on the board, or do alarming things with dictionaries? This might influence how you draw him in the schoolroom. Or find something like this writing-blank from 1810 that shows (idealised) schoolroom scenes of the time, or this hilarious print depicting classroom chaos from circa 1825!

What about when he’s elsewhere? When he goes to London to meet parents and new boys? When he’s at home with Bridget and the kids? When he nips into town to post a letter or buy some ink?

Here’s where I’m going to leave you. Go forth and find your own things that will inform your own drawings - and have fun with it! And, if you do draw William Shaw, or anybody else using this sort of thing, please show me! Head over to Instagram or Twitter to share whatever exciting things you draw.

Sunday, November 29, 2020

Some books I read this month: November 2020

Remains to be seen whether this will end up as a series or not. Anyway!

The Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c. 1500 - c. 1800

Nigel Llewellyn

Reaktion Books in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1991

Copiously illustrated with all manner of splendid deathly items from visual and material culture: coffin plates, engravings, commemorative portraiture, effigies, monuments, mourning rings, sketches, and loads more. There’s also a few references to things not shown in the book that can be tracked down later.

The text itself has some concepts that can help contextualise death and the mentalities and practices surrounding it. I’m particularly interested in the two bodies - the social body, which is the form of the deceased as remembered by everybody else (such as in commemorative portrayals, epitaphs, and stuff designed for future viewers), and the natural body, which is the bit that rots and has the potential to cause alarm with its decay. The social body, as presented in monuments and what-have-you, could sometimes be used to communicate a revised version of the depicted individual’s life and exploits. Weirdly, history might count as presentation and re-presentation of the social bodies of people in the past, according to historians’ interpretations and their own cultural contexts and all that.

|

The concept of the two bodies concerns image control, reputation, what people in the past wanted their contemporaries and people in the future to remember (or to believe) - that sort of thing.

Yeah, the title says the period the book covers finishes circa 1800, which you’d think would put it a bit too early for my case study, but there’s a fair amount of stuff I’d find useful anyway. There’s a few post-1800 things, and plenty of stuff that I can pull into my work that people of the time would have understood. I came away with loads of ideas, particularly with regard to William and his potentially forthcoming death in Despaired Of - my weird experimental comic in which one small aspect of an incident at Bowes Academy is explored using five different visual languages - basically, William’s life was “despaired of” at one point, and they thought he was going to die, so this book is setting my brain on fire (in the best possible way) with all sorts of wild stuff.

|

| Bridget in a state of neoclassical despondency. |

Pagan Britain

Ronald Hutton

Yale, 2013

Not gonna lie, I’m a fan of Ronald Hutton. I’ve attended a couple of his talks, and I read The Triumph of the Moon in the summer, and, as far as I’m concerned, he says a lot of very sensible things.

Pagan Britain is a good solid overview of belief and its material traces from prehistoric times, through to the Middle Ages, and with a few hints of seemingly pagan practices in later years.

(“What are you reading this for, Ed? This is all well before your case study!” exclaims the reader, much surprised.)

I’m in strong agreement with Hutton’s historiographical angle. He declares his standpoint, respectfully, at numerous points in the book. He acknowledges that there’s multiple interpretations of the traces that are left, and how those interpretations have changed (and will change) over time, and that we’re not going to get the final story of any of it. He presents various interpretations, archaeologists’ arguments, and so on, displaying the pros and cons of them and giving them a fair hearing, and he also shows us his own thoughts on various matters - sometimes he explains which interpretation he prefers, or he reacts with quiet emotion to one of the possible stories of what might’ve happened, rather than hiding and feigning objectivity. Basically, he says a lot of things I agree with! Especially in his conclusion - flippin’ ‘eck, it’s a glorious few pages, brilliant and concise, and can be applied to history in general rather than being limited to the scope of the book.

|

The illustrations in this book are fantastic, and have given me all sorts of ideas for Charley's visual language in Despaired Of.

There’s also the visual side of it. There’s plenty of illustrations, including a lot of prehistoric rock carvings, abstract motifs, and representational art. There’s drawings or photographs of amazing things regularly throughout the book. Interestingly, the figures aren’t always directly referred to in the text - I didn’t notice any “see fig. 24” or anything - so the images run alongside the text, and could be viewed almost as a separate essay in their own right. This book has been vital for some of the sections of Despaired Of - one of the characters has an almost prehistoric visual language, in a recontextualisation away from the early 19th century setting.

|

| Charley confronts a metaphorical wolf that's been saying nasty things to him. Told you Despaired Of is weird. |

Witches & Wicked Bodies

Deanna Petherbridge

National Galleries of Scotland in association with the British Museum, 2013

This is a catalogue to accompany an exhibition (that, of course, I missed) and it’s full of depictions of witches, from the Renaissance to the early 21st century.

The images provide a fascinating exploration of how witches were usually depicted by artists in order to convince their audience that they were definitely evil, although these works probably acted as further evidence confirming some of that audience’s pre-existing suspicions. They might’ve said things like ‘Those witches are definitely up to no good - I saw a picture of it!’

And what type of people are the witches in the illustrations? Almost always female, typically either quite elderly and rather unprepossessing, or youthful and somewhat provocative. Both of these depictions are intended to communicate the evils of witches: the ugliness of the more venerable ones is equated with their wickedness, while the young witches are intent on ensnaring blokes with magic spells and sexiness. (It seems that people in the past were a bit scared of women having any sort of power. I hope we’ve moved on from that way of thinking.)

|

This is my favourite image in this book - The Weird Wife o’ Lang Stane Lea (1830) by James Giles (1801 - 1870). I love this because there’s a witch (of course!), there’s a megalithic monument, there’s the moon and (presumably) Venus in a wonderful sky, there’s dramatic light and shade - there’s all sorts of narrative potential in this painting, things to wonder about, especially with regard to what secret things the witch might’ve just done - and it was painted during the early 19th century. Wins big points from me.

What if you’re not into witchery? This book will show you a curated group of images that document (often negative) views of women’s bodies over a set period of time. Or you could read it with the illustrator’s eye, and look for things that you can borrow or subvert in your own drawings, as a reaction to the images you’ve just seen. Or you could see how methods of image-making change over time, and what media gives the most striking results for the creator’s intent for the image. Or you could have a close look at the images in terms of their material culture, and see what sort of things people wore (or didn’t, there’s a lot of nudity, but we can all handle it like grown-ups) or associated with occult practices.

Wednesday, November 25, 2020

Lines on a Page - watch the presentation and read the paper!

Alrighty, so I've managed to record the presentation for my paper, Lines on a Page: Representations and Interpretations!

(It was originally meant for an internal online conference with the School of Art and the School of Media, but I had my appendix removed in the small hours of the day that the conference was scheduled for, so I couldn't actually attend...)

And here's links to the paper:

If you can't access it, DM me on Instagram - the most reliable way to contact me - and we'll sort something out.

(The paper is illustrated, if that's any further incentive to read the thing! But I'm an illustrator - what else would I do?)

Monday, November 9, 2020

About

I’m Ed, and I’m doing my PhD in Illustration with History at the University of Gloucestershire.

My project is titled Historical deconstruction and re-creation by narrative illustration, evoking the multiplicity of unheard narratives within historical experience.

Let’s unpack that:

Historical deconstruction: I’m a deconstructivist historian. As far as we’re concerned, there is no final single truth in history; there is no one story; there is no objectivity; there are multiple narratives, multiple truths, and multiple interpretations; the historian themself is central to the creation of meaning within history; and what’s left in the historical record (the ‘sources’/ traces of the past) will not tell you ‘the facts’.

Re-creation by narrative illustration: so I’m communicating stories by drawing. I’m not trying to accurately reconstruct the past, but to create my interpretations of it.

Evoking: like I just said, I’m not aiming for 100% accuracy. I’m aiming more to suggest stuff rather than state it definitively.

The multiplicity of narratives within historical experience: there is no one single narrative about any historical event because there’s usually a bunch of different people involved, and they’ll all have their own version. Of course, not all of these stories will have survived, so I’m using drawing to suggest what these stories of these people’s experiences might have been like.

My project is interdisciplinary (combining my two disciplines, Illustration and History) and practice-based (it’s based around my practice as an illustrator). I’m integrating illustration methods and strategies with historical practice and theory, and conducting drawing-based explorations into historiography. The project is also very reflexive - there’s a lot of stuff about my personal practice, and how I relate to the stuff I’m researching.

|

| From a pamphlet about the project from 2019. |

I’m using a specific historical case study for my investigations. This is William Shaw’s Bowes Academy, which he ran under sole ownership from 1814 until 1840. This was one of the Yorkshire schools - a group of boarding schools, mainly in Teesdale (then North Yorkshire, but now part of County Durham), which mostly ran from c. 1750 to c. 1850, and which typically aimed at middle-class parents in London.

Shaw’s Academy is the most well-documented of the Yorkshire schools, and operated when they were at their most popular. It was also pretty big - at one point, there were between 260 to 300 boys present.

I’m mainly interested in the social relations of people at the Academy. I’m looking at William Shaw and his family, members of staff (both in the school and domestic), and the boys themselves; I’m also expanding my investigation to look further afield, such as William’s social connections and the parents in London and elsewhere.

What do I hope to do with all this? I want to revolutionise the discipline of history. Haha! That sounds big. I want to help open it up for people whose first mode of communication isn’t necessarily based around writing. I want to encourage people to explore the vast potential of lost narratives within historical experience. I want to see other researchers, further down the line, take some of my methods and apply those to their own work, generating a broader understanding of their own disciplines and the narratives contained (or hidden or excluded) therein.

Also, I want to conduct the deepest investigation of Shaw’s Academy to date. I want to get into areas that other researchers have not considered, and to dig stuff up and make suggestions that make people think twice. (Right now I’m thinking a lot about plausibility, and making an audience act like historians and question and interpret everything.)

And what about me? I got my BA and MA in Illustration at the University of Gloucestershire in 2015 and 2017 respectively. I’ve done a couple of commercial jobs here and there, but I want to show that illustrators can do research too, and we don’t have to go into the industry. I no longer do commissions.

In my spare time, I do further research, and more drawings, and a bit of writing, and I’m a member of my local fitness group and the local history society. (All meetings now conducted online.)

Anyway, that’s your introduction. I’m going to use this blog - when I remember - to show stuff from my project, and probably some extra stuff too. Sketchbooks, work in progress, secret things, excursions (within reason), that sort of business.

I'm fairly active on Instagram - follow me: @Ed.smike

But I'm only sporadically active on Twitter: @Ed_smike

Characterisation of Charley and Ann - or, Beauty and Sublimity

[Looks like I'd started writing this in 2021, and only now I am getting round to posting it. Hang about, we've got the word "su...

-

[Looks like I'd started writing this in 2021, and only now I am getting round to posting it. Hang about, we've got the word "su...

-

I was using this one right at the start of trying to get the PhD off the ground! So a lot of the front of it is very unexciting old notes ab...

-

The pile! I'm making posts about all these! Click on the links below to see some of the most relevant/ significant/ interesting/ fun bit...