Earlier this month, I went to the theatre - without leaving the house! The Society for Theatre Research held an online performance of Edward Stirling’s 1838 adaptation of Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby, with a versatile and enthusiastic cast. There was a brief contextualising explanation at the start, and then the performance kicked off - and what a performance it was - and you can watch it here!

The company all had great fun performing, and all communicated their characters very effectively over Zoom, with appropriate subtleties and exuberances as required. They were very properly attired, with a splendid profusion of hats and other accoutrements, and a fine range of suitable props - sometimes it looked like a big Victorian video-chat party, which I suppose it was - and it was all excellent!

The script was that of the first ever adaption of Nickleby, and was first performed well before Dickens had even finished the novel. (The whole text of the play is available to read here!) Every month from March 1838 to September 1839, a new instalment of Nickleby would come out, containing a few chapters, two illustrations by Dickens’ mate Phiz, and a bunch of adverts and extra bits, and each instalment would cost one shilling (except the last, which was a double number and cost two). In November 1838, Stirling’s adaptation premiered at the Adelphi Theatre, on the Strand, in London.

Given my research interests, this post is mainly going to be about contextualising the first stage depiction of Wackford Squeers, comparing this with Nickleby and with some fragments of information about Yorkshire schools, and some ideas I had after watching the STR's performance.

The play opens in the Saracen’s Head, Snow Hill - a coaching inn - and we’re immediately introduced to Mr. Squeers (played by Mark Fox in the STR's version), a Yorkshire schoolmaster who quickly establishes himself as a villain, generally being disagreeable (with a façade of benevolence) in ways that Nickleby readers will recognise from his first appearance in the novel in Chapter 4.

Upon the arrival of Ralph Nickleby (played by Steve Fitzpatrick) and his nephew Nicholas (Hugh-Guy Lorriman), Squeers begins to reel off his advert, as he does in the book, and which the 1838 audience would have recognised from schoolmasters' adverts they'd have seen in the newspapers.

The schoolmaster also explicitly mentions two towels in the first scene, while in Act 1 Scene 3, he says that the inhabitants of Dotheboys Hall get up at seven in the morning during winter, and six in the summer. However, comparing this with Nickleby, in Chapter 7, he only mentions getting up at seven - nothing about six - and isn't specific about the number of towels. Now, anybody familiar with the finer points of the 1823 ophthalmia trials (in which William Shaw was taken to court by two families for allowing their sons' sight to be damaged) will recognise the two towels - Shaw only provided two for his entire school of nearly 300 boys. We don't have the precise getting-up times at Shaw's place, but we have these times from other schoolmasters; for example, Mr. Simpson of Woden Croft, just up the road from Shaw's, specified that his scholars should get up at 5:30 in the summer and 6:30 in the winter. I reckon Stirling Knew Things.

Squeers also recites a list of items that the boys need to bring to his establishment, as he does in his initial appearance in the novel, and which echoes a list on a card of terms from William Shaw's Academy that turned up in an issue of the Dickensian. (And I am much vexed as I don't know which issue it's in and I can't cite it properly - I have lost the original PDF - iCloud has taken to betraying me of late - but I will get hold of it again.)

I’m not sure whether Yorkshire schoolmasters had appeared on the stage before Stirling's adaptation, but, if not, this is likely to have been the first time a lot of the audience had encountered a depiction of them outside their newspaper adverts, word-of-mouth tales, and Phiz's Squeers in print-shop windows.

This page from the Adelphi Theatre Calendar says that a ticket for a seat in the upper gallery cost one shilling, two for a seat in the pit, and four for a seat in a box. If you spend one shilling on an instalment of Nickleby, you get a few chapters, a couple of illustrations, etc., whereas if you spend it on a theatre ticket, you get a few hours of a variety of different entertainments, and you don't have to fork out for all the other instalments of the novel to find out what happens next in the story. There might've been people in the audience who were reading the novel and wanted to see it acted out before their very eyes, and there might've been people who went for a night out or to see some other anticipated performance and went home with a head full of Dickens, and there might've been people who were like "I've not read it, but I'll watch the adaptation".

I reckon that this play could’ve potentially contributed to public perceptions and opinions of Yorkshire schoolmasters and their establishments. There’s a few scenes at Dotheboys Hall - which would’ve been depicted wonderfully grim on stage, as the early 19th century theatre delighted in impressive sets -complete with the forbidding Mrs. Squeers (in the STR's 2020 version, played with vigour by Sunita Dugal) and a cortège of miserable boys (mainly voiced by the STR's Eileen Cottis) - which would have communicated a version of Dickens and Phiz’s interpretation of the Yorkshire schools to a broader audience.

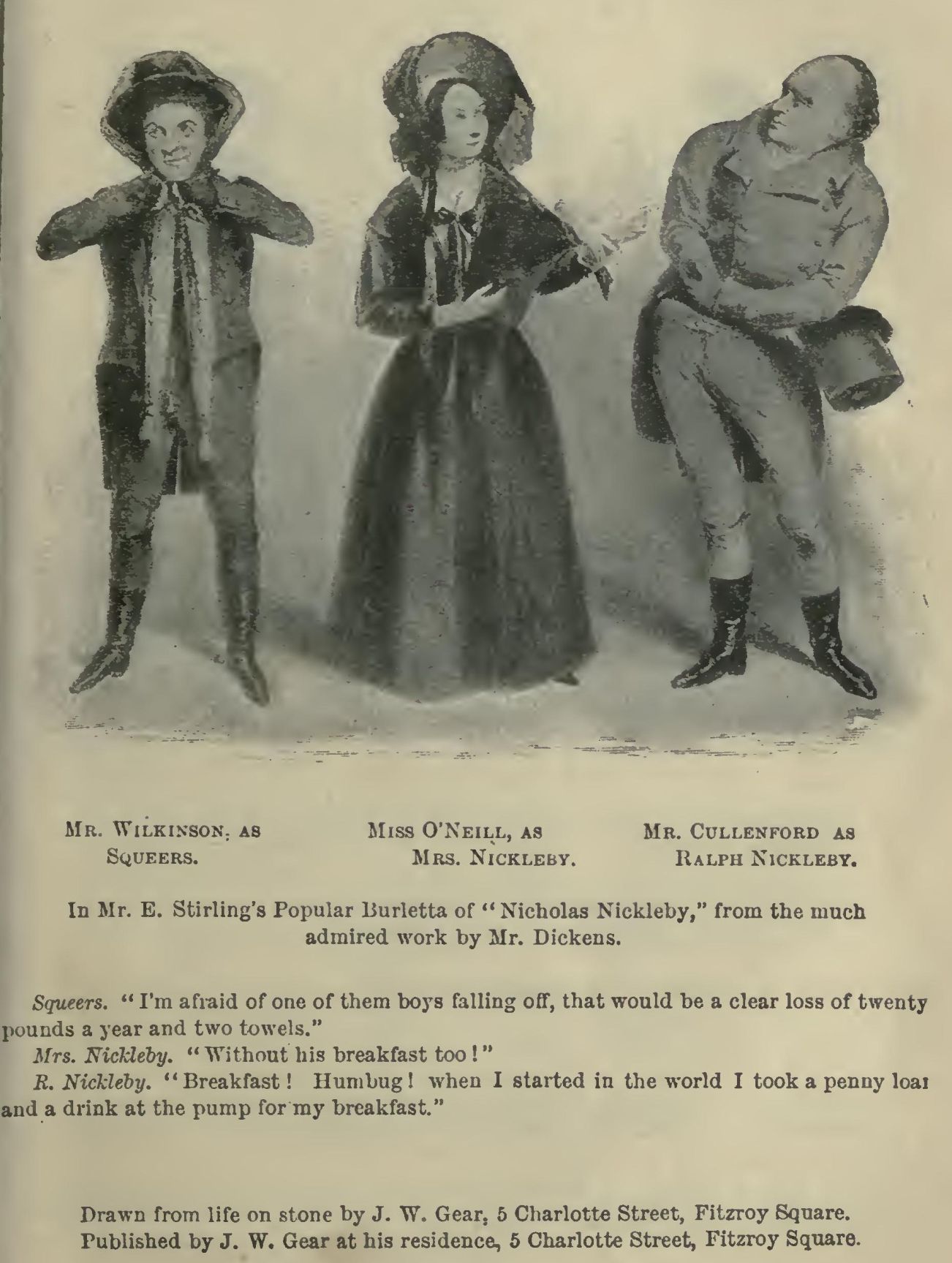

The original 1838 Squeers was played by James P. Wilkinson, who joined the Adelphi’s company in 1819, and whose last performance was in 1845. Having quickly eyed his entry on this page, he seems to have done a lot of burlettas, comedies, and similarly amusing productions, but he wasn’t unfamiliar with more serious dramas and melodramas.

|

| Here's a page from Project Gutenberg's edition of Nickleby - Gear's illustrations are in the front, accompanied by quotes from the play rather than from the book. |

Given the presentation of Squeers at the start of the play, and especially how Stirling’s production’s full title was Nicholas Nickleby - A Farce in Two Acts, the audience might’ve expected the schoolmaster to be more comedic. And yes, the character is funny, in both the original Nickleby and Stirling’s adaptation, but his malevolence soon becomes one of his distinguishing features (after the solitary eye). They certainly expected it of the original Smike, played by Mary Anne Keeley, a popular actress who specialised in comedy; the STR’s introduction explained that, as stated in Keeley’s autobiography, when she first appeared on the stage in the role, the audience expected comedy and roared with laughter - but, after she’d delivered a speech (about being trapped at Dotheboys Hall, with a lot of the “Pain and fear!” bit from Chapter 8) the audience fell dead silent, apart from a single stifled sob…

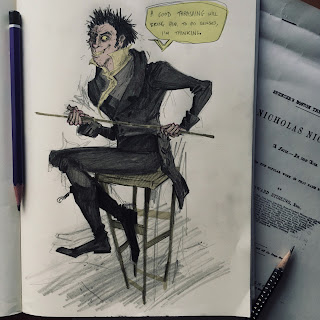

On Sunday night, the actors explained that the original script contains directions for tableaux vivants - everybody on stage freezes and holds a position, usually in silence - a good modern example is those scenes in A Field In England (directed by Ben Wheatley, 2013, would recommend). In the original performances of Stirling’s adaptation at the Adelphi, the tableaux vivants were arranged to be as close to Phiz’s illustrations as possible. So, thinking about Act 1 Scene 1 (in which we are introduced to Mr. Squeers), that tableau could have represented this scene, but he’d be dealing with breakfast rather than mending a pen:

(As an illustrator, I think this is pretty great. From my perspective, it’s like saying that the illustrator’s work is as vital to understanding the narrative as the author’s. Eh. I’m biased towards my vocation and my fellow practitioners. And I suppose it’s convenient for actors if they’ve got a visual framework ready made for them, and some of the audience will recognise the scenes from their copies of Nickleby, or from the engravings displayed in print-shop windows.)

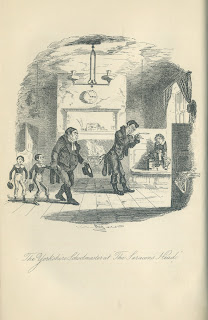

To my astonishment, the STR actors did a tableau vivant! On Zoom! Everybody in separate locations! In the middle of the scene in which Smike (played by Rebecca Farrell) is captured and Nicholas batters Squeers - that’s not a spoiler, it’s probably the most well-known bit of the story - but the way that they did it was fantastic, quite ingenious and very professional. In the original production, this tableau was based on Phiz’s illustration to Chapter 13.

|

| Imagine this - ON STAGE. |

Alright, yes, this isn’t going to be exactly like what the first audiences would’ve seen back in 1838 - if you want to see exactly what they saw, then you’ll have to invent reliable time travel, but even then you wouldn’t have access to all their cultural references and mentalities and associations and what-have-you, so you won’t get exactly what they’re getting. A step down from time travel, full-scale historical experience replication would take up a lot of resources - rebuilding the Adelphi precisely as it was, finding the scripts for the rest of the evening’s performances, etc. - although it would be fun - anyway! This was a very 2020 version, conducted over Zoom (with one or two technical incidents, but that's all part of the video-chat experience, and the show went on regardless) and it was brilliant.

So, yeah. Not only was it a good night in, but the Society for Theatre Research’s performance might’ve given me a few clues and ideas with regard to public perception of Yorkshire schoolmasters.

Watch the full STR production here!

(Yes, I am including the link twice, because it was that good.)

More information from the STR.

STR's cast list, and list of scenes.

The British Library has a playbill that mentions Stirling's adaptation from February 1839 - the play was still in its first season, and ended up running for nearly a hundred nights.

The British Library also has an original script, with a frontispiece.

No comments:

Post a Comment